Lesson 2: Bridges & Barriers to Trade

- >

- Teachers

- >

- Teacher Resources

- >

- Lesson Plans

- >

- Issues of International Trade

- >

- Lesson 2: Bridges & Barri…

Download IIT Lesson 2 Guide

Lesson Overview

In spite of general recognition that trade creates wealth, the history of international trade is largely a series of attempts by different nations to gain some elusive advantage in the trading game by erecting trade barriers. In contrast to the general historical trend, the last two decades of the twentieth century were characterized by a growing number of trade agreements and the lowering of trade barriers. The result is that at the turn of the 21st century, it was possible to assert that international exchange was freer than at any other time in history. Lesson 2 reviews the vocabulary of trade restriction before analyzing the impact of trade-inhibiting policies and moving on to the more important question of why the urge to erect barriers seems so resistant to the economic logic that restricting trade restricts the creation of wealth.

Concepts

| Trade barrier | Tariff | Subsidy |

| Trade agreement | Quota | Protectionism |

| Embargo | Sanction | Public Choice Theory |

Content Standards

Standard 5: Students will understand that: Voluntary exchange occurs only when all participating parties expect to gain. This is true for trade among individuals or organizations within a nation, and among individuals or organizations in different nations.

Students will be able to use this knowledge to: Negotiate exchanges and identify the gains to themselves and others. Compare the benefits and costs of policies that alter trade barriers between nations, such as tariffs and quotas.

Benchmarks, Grade 8: At the completion of grade 8, students will know

- Free trade increases worldwide material standards of living.

- Despite mutual benefits from trade among people in different countries, many nations employ trade barriers to restrict free trade for national defense reasons or because some companies and workers are hurt by free trade.

- Imports are foreign goods and services purchased from sellers in other nations.

- Exports are domestic goods and services sold to buyers in other nations.

- Voluntary exchange among people or organizations in different countries gives people a broader range of choices in buying goods and services.

Benchmarks, Grade 12: At the completion of grade 12, students will know

- When imports are restricted by public policies, consumers pay higher prices and job opportunities and profits in exporting firms decrease.

Standard 6: Students will understand that: When individuals, regions, and nations specialize in what they can produce at the lowest cost and then trade with others, both production and consumption increase.

Students will be able to use this knowledge to: Explain how they can benefit themselves and others by developing special skills and strengths.

Benchmarks, Grade 8: At the completion of grade 8, students will know

- Like trade among individuals within one country, international trade promotes specialization and division of labor and increases output and consumption.

- As a result of growing international economic interdependence, economic conditions and policies in one nation increasingly affect economic conditions and policies in other nations.

Benchmarks, Grade 12: At the completion of grade 12, students will know

- Individuals and nations have a comparative advantage in the production of goods or services if they can produce a product at a lower opportunity cost than other individuals or nations.

- Comparative advantages change over time because of changes in factor endowments, resource prices, and events that occur in other nations.

Standard 17: Students will understand that: Costs of government policies sometimes exceed benefits. This may occur because of incentives facing voters, government officials, and government employees, because of actions by special interest groups that can impose costs on the general public, or because social goals other than economic efficiency are being pursued.

Students will be able to use this knowledge to: Identify some public policies that may cost more than the benefits they generate, and assess who enjoys the benefits and who bears the costs. Explain why the policies exist.

Benchmarks, Grade 12: At the completion of grade 12, students will know

- Although barriers to international trade usually impose more costs than benefits, they are often advocated by people and groups who expect to gain substantially from them. Because the costs of these barriers are typically spread over a large number of people who each pay only a little and may not recognize the cost, policies supporting trade barriers are often adopted through the political process.

Key Points

Trade Restrictions – Erecting Barriers to Trade

- There is general agreement among economists that trade creates wealth.

- Restricting trade thus reduces the growth of wealth.

- Although trade barriers take many forms, the most common are tariffs and quotas.

- Both limit competition and trade and therefore reduce overall wealth.

- A tariff is an import tax.

- While a tariff generates government revenue, its more important effect is to raise the price of the imported product.

- Its purpose is to “protect” the domestic product from competition by insuring that foreign products are the higher-priced, and therefore less desirable\ alternative.

- A quota is a limitation on the quantity of a product that may be imported.

- Although its effect is indirect, a quota is similar to a tariff in that it raises the price of the imported product.

- Restricting the supply puts upward pressure on the price of the import, making the domestic product the lower-priced alternative.

- Unlike tariffs, quotas do not generate government revenue.

- Although its effect is indirect, a quota is similar to a tariff in that it raises the price of the imported product.

- The arguments for tariffs and quotas focus on the “protection” of domestic industries.

- The “infant industries” argument suggests that new industries need time to establish themselves without the pressure of foreign competition. Questionable assumptions of this argument include:

- That there are necessarily higher costs in the start-up phase of an industry and that there is good reason for a domestic firm to enter a market being served by imports.

- If there is insufficient profit potential to attract a domestic producer to bear the start-up costs (whatever their level), it seems reasonable to continue to allow the market to be served by foreign producers.

- To protect the domestic producer with tariffs or quotas decreases supply, raises prices to consumers and thereby subsidizes the income of the domestic industry.

- Lower-priced foreign labor gives foreign producers an unfair advantage.

- Lower-priced foreign labor is a reflection of lower productivity. Higher domestic wages are a function of the higher productivity of U.S. workers. The higher output per man-hour by domestic workers makes their product competitive with imports.

- We frequently find that similar products are produced both overseas and domestically for consumption in the U.S.

- Steel is a good example—In 2018 China was the number one steel producer in the world followed by India. The U.S. was number 4. While U.S. labor is more expensive than labor in India or China, U.S. steel makers can compete with Chinese and Indian steel makers because U.S. workers are more technically skilled and have more capital and resources available to them. In other words, they have higher rates of productivity.

- That there are necessarily higher costs in the start-up phase of an industry and that there is good reason for a domestic firm to enter a market being served by imports.

- The “infant industries” argument suggests that new industries need time to establish themselves without the pressure of foreign competition. Questionable assumptions of this argument include:

- The “essential industries” argument suggests that there are some sectors of our economy (agriculture or plane manufacturing, for example), that are essential to the defense and well-being of our country.

- This argument is built on the presumption that economic self-sufficiency is desirable and that the interdependence engendered by international trade weakens the United States, especially in times of war.

- The questionable assumption of this argument is that dependence on foreign production will leave the U.S. vulnerable in times of need because foreigners will have the ability to withhold key products.

- Historically, this has proven not to be the case.

- It’s important to remember that interdependence is a two-way street.

- Most importantly, the question of what constitutes a “key” industry is difficult to answer.

- It’s not always possible to determine or agree on what industries are essential or will be essential in the future.

- There are huge incentives for industries to lobby for an “essential” designation, regardless of their actual role, which should make us skeptical of any such designation.

- The “trade-costs-jobs” argument suggests that imports allow low-wage foreign producers to “steal” domestic jobs.

- Questionable assumptions of this argument include:

- The mistaken belief that foreign wage rates are something other than a reflection of differences in productivity, and

- The belief that replacement of domestic production with foreign production reduces the total number of jobs in the United States.

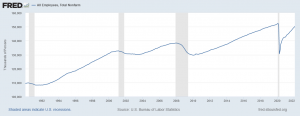

- Bureau of Labor Statistics data indicates that during the 1990s period of falling trade barriers, employment in the U.S. rose by over 15 million, the number of unemployed fell, and the percentage of unemployment fell.

- Increased jobs after NAFTA was signed into agreement in 1994

- Questionable assumptions of this argument include:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=n3QV

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=n3QV

Bureau of Labor Statistics data. Compiled for the FTE by Dr. Jamie Wagner Economics Professor and Director, UNO Center for Economic Education, University of Nebraska at Omaha

- Other forms of trade barriers include anti-dumping policies, embargoes, sanctions, and subsidies.

- “Dumping” is said to occur when a foreign producer sells a product in the U.S. at a price below production cost.

- If domestic producers believe that foreign competition is “dumping,” they can call for U.S. Dept. of Commerce investigation. If the government finds merit to the claim, a tariff or fine is levied to make the import competitive with the domestic product.

- The theory suggests that foreign firms do this with the intent of driving domestic producers out of business and then raising prices.

- The problem with this line of reasoning is that it ignores the reality that high-priced imports call domestic producers back into the market.

- Attracted by the profit potential, domestic competitors re-enter the market.

- The problem with this line of reasoning is that it ignores the reality that high-priced imports call domestic producers back into the market.

- The other problem is the difficulty of establishing even one confirmed case of dumping.

- Usually, the standard for dumping is if the product sells for less in the U.S. market than in its home market. However, this price differential may have very little to do with the cost of production.

- Demand may raise the price in a foreign market, even though costs of production may be lower than they are in the U.S.

- We often see domestic products selling for different prices in different regions of the country, and we aren’t suspicious.

- Regional price differences usually occur because demand – for snow shovels or suntan lotion for example – is either higher or more responsive to price changes in some places than in others.

- The lack of any way to definitively prove that dumping is occurring means that the determination is often arbitrary, reflecting effort by a domestic producer to gain a competitive advantage.

- EXAMPLE: In November 2017 President Trump announced an 18% anti-dumping duty on Canadian softwood lumber exports. The reason was due to an “unfair subsidy” from the Canadian government which allowed loggers to cut down trees on government-owned land for lower rates. The duty was meant to protect the American lumber industry and it sent lumber prices to a 23-year high. In April 2019 the World Trade Organization (WTO) said that the U.S. violated international trade rules and inappropriately calculated the anti-dumping duty on the Canadian softwood imports. If the ruling stands the U.S. will be required to roll back some if it’s restrictions on Canadian lumber imports. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-04-09/wto-delivers-mixed-ruling-in-u-s-canada-lumber-dispute

- EXAMPLE: In the late 1980s, domestic golf cart producers claimed that Poland was dumping carts on the U.S. market. The Department of Commerce then had to determine the “price” of production in a communist country that had administered prices. To do this, they used a “constructed value,” estimating the cost and then adding a percent profit to determine the producer’s home country market price equivalent. Absent market wages, the Commerce Department used labor rates in Spain and applied them to the estimated length of time for Polish workers to make golf carts. (Polish golf cart story taken from The Choice – A Fable of Free Trade and Protectionism, by Russell Roberts. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001, p. 78.)

- Usually, the standard for dumping is if the product sells for less in the U.S. market than in its home market. However, this price differential may have very little to do with the cost of production.

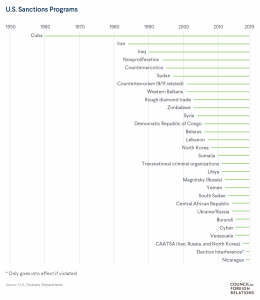

- Trade sanctions are a diplomatic tool used to apply pressure to a country without engaging in armed conflict.

- The general category “trade sanctions” includes embargoes, boycotts, and denial of financial relations.

- As President Woodrow Wilson noted in 1919, “A nation boycotted is a nation that is in sight of surrender. Apply this economic, peaceful, silent deadly remedy and there will be no need for force. It is a terrible remedy.”

- The current list of U.S. sanctions can be found on the U.S. Department of the Treasury website: https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/programs/pages/programs.aspx

- The general category “trade sanctions” includes embargoes, boycotts, and denial of financial relations.

- “Dumping” is said to occur when a foreign producer sells a product in the U.S. at a price below production cost.

Retrieved by Dr. Jamie Wagner on 8/19/19 from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-are-economic-sanctions

-

-

-

-

- U.S. sanctions cover over 25 countries and have been estimated to cost the U.S. economy $20 billion annually in lost exports. (“Sanctions-Happy USA,” by Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Jeffrey Schott, and Kimberly Elliott, in International Economics and International Economic Policy – A Reader, ed. by Philip King Irwin. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000.)

-

-

- An embargo is a prohibition on the export of specified goods to a specified country.

- An embargo is usually a political tool intended to change particular actions or policies of the embargoed nation.

- Examples of targeted policies include human rights violations, support of terrorists, and political oppression.

- “Examples of countries recently or currently under U.S. embargo prohibiting ALL transactions (including imports and exports) without a license authorization include Crimea (region of the Ukraine), Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Sudan, and Syria.” https://www.export.pitt.edu/embargoed-and-sanctioned-countries

- An embargo is usually a political tool intended to change particular actions or policies of the embargoed nation.

- The record of U.S. use of trade sanctions over the past century indicates that President Wilson’s characterization of sanctions as a “terrible remedy” has proven prophetic in ways he didn’t envision:

- While sanctions do seem to have forced change in some instances (the most notable being the end of apartheid in South Africa), they have for the most part proven ineffective and, indeed, often inflict harm on unintended targets.

- They inflict a high cost on the U.S. economy in lost export revenue and jobs.

- They are often ineffective because they are aimed at totalitarian governments that aren’t responsive to world opinion.

- Leaders of sanctioned nations prove willing to allow sanctions to inflict suffering on their people while increasing their own grip on power.

- U.S. sanctions have helped drive down living standards in Cuba to desperate levels almost equaling those of Haiti.

- While sanctions do seem to have forced change in some instances (the most notable being the end of apartheid in South Africa), they have for the most part proven ineffective and, indeed, often inflict harm on unintended targets.

- Trade subsidies help domestic producers by allowing them to sell their products (exports) at a competitive price on the world market.

- Political support for trade subsidies grows from the assumption (often unfounded) that protecting or fostering export industries creates jobs in the exporting country.

- While jobs may be created in export industries, the overall impact of a subsidy is to lower the price of the product for international buyers.

- In effect, domestic taxpayers are paying part of the price.

- The French and British governments subsidized the development of the airbus, successfully creating airline manufacturing jobs in Europe, while providing companies world-wide with airplanes paid for, in part, by French and British tax payers.

- In effect, domestic taxpayers are paying part of the price.

- The persistence of trade restrictions throughout history is best explained by the fact that while such policies limit the creation of wealth in general, they increase wealth and income for specific producers and industries.

- Public choice theory, with its insights into the incentives created by dispersal of benefits and costs, helps us understand the resistance of public policy makers to freeing trade.

- Example: President Trump has added steel and aluminum tariffs with the intent to protect U.S. workers. Tariffs took effect in 2018 and in 2019. As of April, 2019 there was an estimated 381,000 Americans working in the primary metals industry (including steel and aluminum), an increase of 1.2% from the previous year (376,000). https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/30/us/politics/norway-trump-aluminum-tariffs.html

- The resulting situation of concentrated benefits and diffused costs creates different incentives for producers than for consumers.

- For example, the steel and aluminum tariffs were mostly affecting intermediate goods or parts according to the Peterson Institute for International Economics. Therefore, consumers have not felt the brunt of the tariffs and are not likely feeling the negative costs directly. https://www.businessinsider.com/trump-trade-war-tariffs-effect-on-economy-prices-consumer-stocks-2018-7#so-far-trump-has-avoided-hitting-consumer-goods-like-clothes-but-what-he-did-target-could-be-just-as-problematic-6

- Similarly, the original tariff was about 10% (raised to 25% in May 2019). At the original level businesses absorbed much of that initial cost (smaller margins). https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-higher-tariffs-affect-different-industries-11557513451

- Because US steel workers are feeling the benefits of the trade war with more jobs and consumers are not feeling the direct costs (and at this point any costs are low and therefore hard to see) it is unlikely that the trade war will end due to consumers lobbying. Consumers are dispersed and it would be costly and difficult for them to come together to lobby against the tariffs. On the contrary, steel/aluminum workers are easier to organize because they are geographically closer together.

-

Trade Agreements – Clearing Bridges for Trade

- Trade agreements are simply reductions and/or removal of trade barriers among countries. While simple bilateral agreements are a step in the right direction, the complexities of the modern international market (see lesson 6) mean that trade organizations are necessary for significant freeing of trade.

- Forging trade agreements is really the process of removing barriers rather than building bridges.

- In a perfectly free-trade world, there need only be clear property rights and the rule of law for trade to occur and proliferate.

- A long history of trade-protectionism throughout the world means that we now must engage in the process of agreeing to remove the barriers to trade that were erected in years past.

- The best known trade organizations today are:

- WTO, the World Trade Organization (formerly GATT, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade),

- EU, the European Economic Union, and

- USMCA, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (formerly NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement)

- In a perfectly free-trade world, there need only be clear property rights and the rule of law for trade to occur and proliferate.

- Forging trade agreements is really the process of removing barriers rather than building bridges.

WTO – The World Trade Organization

- The World Trade Organization (WTO) was formed from the 100-member General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), organized in 1986.

- In 1993, GATT reached agreements reducing tariff barriers among member nations by 40%.

- In 1997, GATT members formed the World Trade Organization.

- The successor organization, WTO, has much broader agreements and mandates for negotiation and the resolution of trade disputes.

- By mid-year 2016, the WTO had 164 member nations and others were lobbying to join.

- For WTO data, see: http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/thewto_e.html (8/20/19)

- The broader issues of WTO debate now reach beyond tariffs to include the environment (gasoline formulas), intellectual property (software), and health (pricing of essential medicines).

- This broader agenda has brought greater public awareness of the WTO, one result being an increase in protesting the dismantling of trade restrictions.

EU – The European Union

- The European Economic Union (EU), composed of the major nations of Western Europe, had removed nearly all tariffs and quotas among member nations by 1993. The 28 members of the EU in 2019 include:

- Belief that EU policies were successful for all member nations led to the introduction of a common currency, the euro, and to the consolidation of monetary policy in the hands of the European Parliament and the EU Central Bank.

- The importance of the euro lies in the reduction of transaction costs – and the consequent increase in trade – that accompanies the use of a common currency.

- The Euro is the official currency of 19 EU countries—they make up the Eurozone. Within the euro area, the euro is the only legal tender. In the absence of a specific agreement concerning the means of payment, creditors are obliged to accept payment in euros. Parties may also agree to transactions using other official foreign currencies (e.g. the US dollar). They may also agree to use privately issued ‘money’ like local exchange trading systems (e.g. voucher-based payment systems) or virtual currencies (e.g. Bitcoin). These private and business transactions are still subject to taxation law, business law, anti-money laundering law and other general commodity trade rules. However, currencies which are not official within the euro area, are not governed by monetary law.

- For information on adoption of the euro, see: https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/euro/euro-official-currency-euro-area_en (8/19/19)

- To date, the euro seems well accepted despite the diverse cultures and language groups of the member nations.

- The glaring exception has been the United Kingdom, which decided not to be part of the monetary union because of resistance to giving up the English pound sterling and because of concern over the long-term strength of the euro.

- Despite the inevitable problems of working out cooperation between large numbers of nations, the fact that many eastern European and former Soviet Bloc countries are continuing to petition for membership is testimony that the EU is performing its function in increasing trade and wealth among its members.

- General reference sites for the European union: https://europa.eu/european-union/index_en

USMCA—the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (formerly NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement)

The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) was signed replacing NAFTA in November 2018. Once ratified by the 3 countries, it will replace NAFTA. The agreement was spun as a way to deliver American workers from NAFTA which had been taking jobs and money from the US and moving it towards Mexico. The creation of NAFTA in 1994 was an attempt to spread to Mexico the benefits that had been realized by the elimination of tariffs between the U.S. and Canada.

- In 1989, the Canadian – S. Free Trade Agreement went into effect, providing for completely duty-free trade by 1998.

- NAFTA was proposed by the Mexican government of President Carlos Salinas in 1990 to increase trade between Mexico and both the United States and Canada.

- NAFTA resulted in an increased volume of trade among all 3 nations, but most notably between Canada and Mexico.

- According to the International Trade Administration, U.S. – Mexico trade increased approximately134% from 1993-2003 and U.S. – Canada trade increased about 69% in the same period.

- NAFTA resulted in an increased volume of trade among all 3 nations, but most notably between Canada and Mexico.

- The NAFTA proposal sparked a great deal of debate that continues today.

- In the early years of the agreement the magnitude of the agreement was difficult to measure. The first 7 years after the passage of NAFTA constituted the majority of one of the longest economic expansions in U.S. history, with high economic growth rates, low rates of unemployment, and very low inflation.

- By 2001, the two sectors most directly affected by NAFTA were agriculture and apparel manufacturing.

- Trade volume between the U.S. and Mexico increased approximately 16% in the decade after NAFTA was signed.

- However, it should be noted that this is not a 16% increase in total trade volume for the U.S., as some was merely a shift in apparel manufacturing from Asia to Mexico as a result of tariff reductions.

- With now a two-decade record, the positive impact of NAFTA is clear and has generated substantial new opportunities for the US—including workers, farmers, consumer, and businesses.

- Trade with Canada and Mexico supports nearly 14 million American jobs, and nearly 5 million of these jobs are supported by the increase in trade generated by NAFTA.

- The expansion of trade unleashed by NAFTA supports tens of thousands of jobs in each of the 50 states—and more than 100,000 jobs in each of 17 states.

- Since NAFTA entered into force in 1994, trade with Canada and Mexico has nearly quadrupled to $1.3 trillion, and the two countries buy more than one-third of U.S. merchandise exports.

- U.S. manufacturers added more than 800,000 jobs in the four years after NAFTA entered into force.

- Canadians and Mexicans purchased $487 billion of U.S. manufactured goods in 2014, generating nearly $40,000 in export revenue for every American factory worker.

- (See Lesson 4 for a full treatment of the labor issues of international trade.)

- A second concern related to the belief that greater environmental damage would result from industries relocating to Mexico to escape American pollution control regulation.

- There is no evidence that this has, in fact, taken place. Studies referenced by Michael J. Ferrantino of the International Trade Administration suggest that firms appear to move in response to labor-productivity concerns rather than to escape environmental regulation. (“International Trade, Environmental Quality and Public Policy” by Michael J. Ferrantino, in International Economics and International Economic Policy – A Reader, ed. by Philip King Irwin. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2000.)

- Additionally, there is evidence that firms that do relocate take with them the technology of their home country. In effect, the host nation thus imports higher pollution standards by attracting foreign firms.

- (See Lesson 5 for a full treatment of the environmental issues associated with international trade.)

- The freeing of trade in the late 20th/early 21st century has not been restricted to the western hemisphere; U.S. efforts to reduce or remove trade barriers with Asian countries continue, but are often complicated by social and political issues.

- Japan, Korea, and (increasingly) China are important U.S. trading partners.

- Issues that add to the complexity of negotiations include:

- patent rights – especially to intellectual property;

- labor issues, including child labor and slavery;

- human rights concerns; and

- pollution and resource management issues.

Caveats and Conclusions

It is difficult to quantify exactly how much wealth has been created by international trade. Because trade encourages specialization, which in turn causes increases in productivity, some of what are referred to as gains from trade are actually gains from increased productivity. Since both trade and productivity contribute to wealth, it isn’t always clear which caused what portion of the increase. It must also be acknowledged that although international trade is freer than at any time in our history, significant barriers remain. The world is still entangled in tariffs and quotas, and currently confronts economic, environmental, cultural, and human rights issues in trying to create more bridges to the wealth that trade creates. The caveats acknowledged, it is important to emphasize that the relationship between the trend toward freer trade and the growing wealth of participating nations is both real and significant.

Lesson 2 Activities:

- Lesson 1: The Basics Still Apply: Domestic or International, A Market Is a Market

- Lesson 1 Activity: The Magic of Markets

- Lesson 1 Activity: Tag Check

- Lesson 2: Bridges & Barriers to Trade

- Lesson 2 Activity: Tic-Tac-Toe Tariff

- Lesson 2 Activity: U.S. Sugar Policy

- Lesson 2 Activity: The Euro

- Lesson 3: Trade & Labor: Sweatshops

- Lesson 3: Trade and Labor: Sweatshops

- Lesson 4: Trade and Jobs

- Lesson 4 Activity: Giant Sucking Sound

- Lesson 5: Trade and the Environment

- Lesson 5 Activity: Trash

- Lesson 6: The Balance of Payments Always Balances

- Lesson 6 Activity: The Balance of Trade Always Balances

- Lesson 7: International Monetary Exchange

- Lesson 7 Activity: Foreign Currencies and Foreign Exchange

- Resource List

FTE: Celebrating 50 Years of Excellence in Economic Education

2025 is a special year for the Foundation for Teaching Economics (FTE), as we celebrate our 50th anniversary. In 1975,…

The Economic Way of Thinking: The Key to Financial Literacy

Professor Jamie Wagner discusses how economics is the key to financial literacy. She is a Professor and Teaching Fellow with…

FTE Staff Spotlight – John Buck

As society evolves and transforms, so must world leaders – a fact that John Buck is aware of and has…