Lesson 1, Part 1: Defining Terms – Poverty and Capitalism

- >

- Teachers

- >

- Teacher Resources

- >

- Lesson Plans

- >

- Is Capitalism Good for the Poor?

- >

- Lesson 1, Part 1: Defining Ter…

Part 1: What is Poverty and Who are the Poor?

Download Lesson 1 .doc file – includes all figures and sources

Part 2: Capitalism: Institutional Building Blocks

Concepts

- absolute poverty

- income

- relative poverty

- wealth

National Voluntary Content Standards in Economics

The background materials and student activities in lesson 1, part 1, address parts of the following national voluntary content standards and benchmarks in economics. Students will learn that:

Standard 13: Income for most people is determined by the market value of the productive resources they sell. What workers earn depends, primarily, on the market value of what they produce and how productive they are.

- Changes in the structure of the economy, the level of gross domestic product, technology, government policies, and discrimination can influence personal income.

- Two methods for classifying how income is distributed in a nation – the personal distribution of income and the functional distribution – reflect, respectively, the distribution of income among different groups of households and the distribution of income among different businesses and occupations in the economy.

Standard 15: Investment in factories, machinery, new technology, and the health, education, and training of people can raise future standards of living.

- Economic growth is a sustained rise in a nation’s production of goods and services. It results from investments in human and physical capital, research and development, technological change, and improved institutional arrangements and incentives.

- Historically, economic growth has been the primary vehicle for alleviating poverty and raising standards of living.

Overview

Thinking about and discussing world problems in the classroom is made productive by adopting procedures and methodologies that lead to increased understanding of the complexities inherent in controversial issues. A foundation for the open discourse that produces informed opinions lies in setting the parameters for discussion. Impatience may tempt us to bypass the seemingly mundane exercise of defining terms, but time spent in clarification is rewarded – although those rewards, in miscommunications eliminated and sidetracks avoided, may be apparent only in hindsight. The exercise of building an agreed-upon working vocabulary is particularly important when the terms of discourse are loaded with nuance and tossed around in every-day conversation in countless ways to serve countless purposes.

The goal of lesson 1 is to propose a working vocabulary. The two-part background outline defines “poverty” and “capitalism” in economic terms. In the accompanying three classroom activities, students first confront the slippery nature of their own use of the terms and then proceed to construct a tacit agreement about what the words will mean as they embark on their classroom investigation of whether capitalism is good for the poor.

The exercise will also help students to focus on world poverty, rather than on the American from about which they have greater knowledge. Learning to distinguish between relative and absolute poverty will give them labels for something they know but may not have found easy to express – that poverty in the United States may look like vast wealth from the perspective of sub-Saharan Africa. Is Capitalism Good for the Poor? is a unit about world poverty, absolute poverty, and lesson 1 is designed to help teachers and students sharpen their focus and zero-in on what they are studying and what they are not. Lesson 1, then, is not intended to address the question of whether capitalism is good for the poor. It is intended to provide the groundwork, so that the investigation intended to answer that question can begin in earnest in Lesson 2.

Key Points

- Overview: According to the World Bank’ World Development Indicators, 2008, 1.3 billion people in the world live in extreme poverty and 22% of the world’s population is poor. Source: World Bank PovcalNet “Replicate the World Bank’s Regional Aggregation” http://iresearch.worldbank.org/PovcalNet/povDuplic.html (2008 data)

- These numbers become useful in discussion of the issue of world poverty only when we know how they were generated and what they mean.

- Terms and concepts:

- The most commonly used measures of poverty are income measures.

- Incomes are money payments the owners of resources earn for contributing their resources to production.

- The most familiar category of income is wages and salaries, the income earned by labor.

- The other 3 categories are:

- rent payments to the owners of natural resources;

- interest payments to the owners of capital; and

- profit to entrepreneurs, who undertake the risk of productive enterprise.

- In developed countries, most people receive their income in the form of money, but in impoverished countries especially, in-kind income is predominant.

- A farmer who plants and harvests grain that his family eats is earning an income; his income is in the form of grain rather than money.

- Because production generates income, total production = total income. Thus, the most common measure of production or output, the GDP (gross domestic product) is also used as a measure of income.

- More specifically, GDP is the commonly used measure of total output or total production, and GDP per capita is the commonly used measure of average income or standard of living.

- GDP (gross domestic product) is the total value of final output produced annually in a nation.

- GDP per capita (gross domestic product per capita) = GDP ÷ population.

- (GNP, or Gross National Product, and GNI, or Gross National Income, are also used to measure income. GDP, GNP, and GNI figures for a particular nation differ only slightly.)

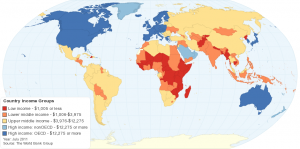

- Income data are frequently used to divide the nations of the world into “high,” “middle,” and “low” income categories, as shown in Map 1 below.

- Map 1: Countries of the World Divided into Low, Middle, and High Income

-

- *GNP – Gross National Product = Total value of annual final production by citizens (domestic and overseas) of a nation

-

- Map 1: Countries of the World Divided into Low, Middle, and High Income

- In economic terms, wealth and income are different.

- Income is a flow of receipts over a period of time – earnings per month or per year.

- Earning an income allows people to acquire the goods and services that make up their standard of living.

- Wealth is an accumulation of past income earned and reinvested. It is best thought of as a stock of the assets people have acquired.

- Income is a flow of receipts over a period of time – earnings per month or per year.

- While wealth per capita is not typically used in measuring poverty, it is important to consider that wealth also affects standard of living.

- For example, income measures of poverty may mistakenly list people as poor because they have low income but enjoy a high standard of living because of their accumulated wealth.

- A retired person who owns a house and a car and lives an active life with travel and entertainment certainly is not “poor” even though her current income may be limited to social security checks or a small pension.

- For example, income measures of poverty may mistakenly list people as poor because they have low income but enjoy a high standard of living because of their accumulated wealth.

- Comparing levels of poverty in different years or different countries requires that the measurement tool(s) be clearly identified and consistent throughout the analysis. Additionally, valid comparisons can be made only in terms of real (as opposed to nominal) values.

-

- Real values are adjusted to eliminate differences that result from inflation. Comparisons of income over time commonly use a base year of constant purchasing dollar value; for example, the income per person in 1950 and today can be compared by correcting for inflation over that period.

- Real values also facilitate comparisons among nations. Income data are converted from local currencies to U.S. dollars using a currency exchange measure called PPP (purchasing power parity).

- The World Bank data in the chart below shows 2010 per capita GNI (gross national income) for many of the poorest nations in the world. Compare the values in the chart to the United States’ per capita income.

- (Note that the PPP values facilitate comparison of actual purchasing power among nations.)

- Table 1: 2010 GNI per capita for a Sampling of the World’s Poorest Nations

Country PPP Atlas Country PPP Atlas Country PPP Atlas Angola 5,460 3,960 Guinea 1,020 400 Papua New Guinea 2,420 1,300 Bangladesh 1,810 700 Guinea –Bissau 1180 590 Rwanda 1,150 520 Benin 1,590 780 Haiti Senegal 1,910 1,080 Burkina Faso 1,250 550 Kenya 1,640 810 Sierra Leone 830 340 Burundi 400 170 Kyrgyz Rep. 2070 830 Solomon Islands 2,220 1,030 Cambodia 2080 750 Lao PDR 2,440 1,040 Sudan 2,030 1,270 Cameroon 2,270 1,200 Madagascar 960 430 Tajikistan 2,140 800 Central African Republic 790 470 Malawi 860 330 Tanzania 1,440 540 Chad 1,220 620 Mali 1,030 600 Togo 890 490 Comoros 1090 750 Mauritania 2,410 1,000 Uganda 1,250 500 Congo, Dem. Rep 320 180 Moldova 33,360 1,810 Uzbekistan 3,110 1,280 Cote d’Ivoire 1,810 1,160 Mozam-bique 930 440 Yemen, Rep. 2,500 1,170 Eritrea 540 340 Nepal 1,210 490 Zambia 1,380 1,070 Ethiopia 1040 390 Niger` 720 370 Zimbabwe 460 Gambia, The 1,300 450 Nigeria 2,240 1,230 United States 47,310 47,340 Ghana 1,620 1,250 Pakistan 2,790 1,050 - Source: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DATASTATISTICS/Resources/GNIPC.pdf Notes: See attached .doc file

- While income measures are both useful and widely used, they do have shortcomings:

- Per capita GDP and GNI are averages, and therefore depict standard of living in very general terms that may hide income disparities within a population.

- Averages – per capita and all others – smooth out differences in the income of individuals and groups, and thus may not accurately portray the material well-being of large portions, or even a majority, of a nation’s citizens.

- Suppose, in the most extreme instance, that 95% of a country’s income went to a ruling family, leaving only 5% for the millions of citizens. In that case, the general poverty of the population would be hidden by the per capita average. (See Appendix 1, “Relative Poverty and Distribution of Income,” download link at bottom of page.)

- Averages – per capita and all others – smooth out differences in the income of individuals and groups, and thus may not accurately portray the material well-being of large portions, or even a majority, of a nation’s citizens.

- Per capita GDP and GNI are averages, and therefore depict standard of living in very general terms that may hide income disparities within a population.

-

- Income is closely tied to consumption. It is derived from output and used for consumption or savings (which is merely delayed consumption), In subsistence economies where savings are non-existent, current consumption = output.

- Consumption (as opposed to output) measurements provide more reliable indicators of standards of living where income data is non-existent or hard to gather.

- Rather than relying on estimated values or assumptions about the level of material well-being implied by dividing GDP by population, consumption measurement is derived from a statistically significant number of household surveys. The survey data about the goods and services the members of the household actually consume are then converted to monetary values.

- Many poverty researchers prefer consumption measures to output-based measurement in developing countries because the data are more precise and can be collected without large government outlays.

- Household surveys also have the advantage of providing a reliable way to account for income-in-kind.

- China and India – until recently the location of a majority of the world’s poor – have large, accurate household surveys going back several decades. More and more developing countries joined them in this practice in the 1990s.

- The World Bank’s consumption survey is the source of the estimate with which we began the lesson: that 1.3 billion people, or 25% of the world’s population, live in extreme poverty

- The consumption data in Table 2, below, reinforce the conclusions reached using the income data in Table 1, above.

- Table 2: Consumption Measure of # of Poor by World Region

-

Regions 2005 2008 East Asia and the Pacific 332 million 284 million Eastern Europe and Central Asia 6 million 2 million Latin America and the Caribbean 48 million 37 million Middle East and North Africa 11 million 9 million South Asia 598 million 571 million Sub-Saharan Africa 395 million 386 million Total 1.39 billion 1.289 billion Reduction in number of poor, 2005-2008: 101 million - Sources: World Bank Poverty and Inequality Database http://databank.worldbank.org/Data/Views/Reports/TableView.aspx (May 1, 2012)

- (Although it is not the focus of this unit, poverty is also frequently measured in terms of social indicators. For a more complete discussion of social indicators of poverty, see Appendix 2, “Social Indicators of Poverty,” download link at bottom of page.)

- The consumption data in Table 2, below, reinforce the conclusions reached using the income data in Table 1, above.

- Consumption (as opposed to output) measurements provide more reliable indicators of standards of living where income data is non-existent or hard to gather.

- Absolute poverty is conceptually and empirically different from relative poverty.

- Absolute poverty is identified by designating a minimum threshold of material well-being. The incomes of the poor fall below the minimum threshold.

- Poverty lines differ among nations, as each designates its own acceptable minimum level of material well-being.

- Thus, poverty lines differ markedly from nation to nation and region to region. (In Map 2, below, poverty lines for India and China have been converted to $US to facilitate real purchasing power comparisons.)

- Map 2: Poverty Lines: Income/Person/Day – US, India, & China (See Map 2 in attached .doc file.)

- Thus, poverty lines differ markedly from nation to nation and region to region. (In Map 2, below, poverty lines for India and China have been converted to $US to facilitate real purchasing power comparisons.)

- Poverty lines differ among nations, as each designates its own acceptable minimum level of material well-being.

- Relative poverty differs from absolute poverty in that it is identified by comparing levels of material well-being experienced by different individuals or groups, rather than by comparing the level of well-being to a standard.

- Since income is not equally distributed among all members of a society, some will be relatively poor and others will be, by comparison, relatively rich

- (“Is Capitalism Good for the Poor?” focuses on the problem of absolute poverty. However, a more detailed introduction to relative poverty is included in Appendix 1.)

- Since income is not equally distributed among all members of a society, some will be relatively poor and others will be, by comparison, relatively rich

- Absolute poverty is identified by designating a minimum threshold of material well-being. The incomes of the poor fall below the minimum threshold.

- World economic history provides a clear picture of decreasing absolute poverty.

- Historically, changes in absolute poverty have been indicated by a population’s increased or decreased ability to acquire particular basic goods and services.

- Researchers investigating changes in absolute poverty are interested in questions such as:

- “How many of the world’s people had access to clean drinking water in 1700? In 2000?”

- “What was the infant mortality rate in 1700? In 2000?”

- “How has life expectancy changed over the last 100 years?”

- Researchers investigating changes in absolute poverty are interested in questions such as:

- Beginning around 1750, western economies began to make significant progress in reducing levels of absolute poverty. (See introductory essay, “A Brief History of Human Progress.”)

- Throughout history, absolute poverty has been the norm. Only in the past two-and-a-half centuries have some nations reached levels of production leading to marked reduction in poverty.

- “If we take the long view of human history and judge the economic lives of our ancestors by modern standards, it is a story of almost unrelieved wretchedness. The typical human society has given only a small number of people a humane existence, while the great majority have lived in abysmal squalor” (Rosenberg and Birdzell 3).

- The 17th century philosopher, Thomas Hobbes, memorably described the life of man as “solitary, nasty, brutish, and short.”

- Modern economic growth began in mid-18th century Europe, and the ensuing economic progress spread, reducing absolute poverty worldwide

- Throughout history, absolute poverty has been the norm. Only in the past two-and-a-half centuries have some nations reached levels of production leading to marked reduction in poverty.

- Since 1750, human society has made consistent inroads against absolute poverty, and improvements have been especially noteworthy in the last quarter century

- For the first time in human history, we are experiencing a sustained decline not only in the percentage of the world’s population that is poor, but in the total number of the poor.

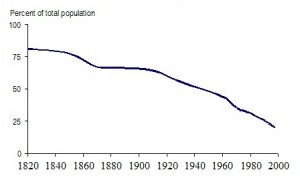

- While it is true that for centuries the total number of poor grew as population grew, it’s important to acknowledge that the increases were not proportional. The percentage of people living in poverty declined as increasing food supplies more than kept pace with increasing population. (See Figure 1, below.)

- Figure 1: Share of World Population in Poverty, 1820-1998*

- Source: Dollar, David. “Capitalism, Globalization and Poverty.” World Bank, 2003. *(This figure comes from a 2003 World Bank report that, as of 2012, has not been updated. However, as other data in this outline indicate, the trend portrayed in the graph continues.)

- Figure 1: Share of World Population in Poverty, 1820-1998*

- Records from 1820 lack precise income and standard-of-living indicators, but the vast majority of people were subsistence farmers whose total consumption would be valued at less than $1/day at current prices.

- Since the early 1800s, the proportion of people living in extreme poverty has declined from 80% to about 17.5% in 1998, with most of the decrease occurring – as Figure 1 shows – during the 20th century.

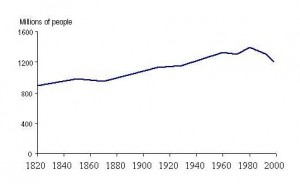

- While the percentage of people living in poverty fell continuously over the 200 year span following 1800, it is true that until very recently, the total number of poor people continued to grow as world population grew. (See Figure 2, below.) Recently, however, even that barrier to reducing absolute poverty has fallen.

- The number of poor in the world peaked around 1980 at an estimated 1.4 billion.

- After 1980, population growth in the world was not sufficient to offset the decline in the percentage of people in poverty, so that not only the percentage but the absolute number of the poor began to fall.

- Globally, the number of extreme poor – those living on less than $1.25/day – has declined by nearly 650 million people since 1981.

- Figure 2: Number of People Living on Less than $1/day, 1820 – 1998*

- Source: Dollar, David. “Capitalism, Globalization and Poverty.” World Bank, 2003. *(This figure comes from a 2003 World Bank report that, as of 2012, has not been updated. However, as other data in this outline indicate, the trend portrayed in the graph continues.

- After 1980, population growth in the world was not sufficient to offset the decline in the percentage of people in poverty, so that not only the percentage but the absolute number of the poor began to fall.

- Recent reductions in absolute poverty have not been uniform worldwide. World totals hide significant regional differences:

- The decline in the poverty numbers shown in figure 2 (up to 1998) is the result solely of developments in China and India.

- Measured against their own poverty lines (see Map 2, p. 8), China and India have experienced declines in both the numbers and percentage of the poor (see Figure 3 in .doc file attached above).

- According to household surveys in China, the number of people with incomes below the Chinese national poverty line declined from 250 million in 1978 to 34 million in 1999. Over 200 million people were raised out of poverty during that 20 year time period.

- Importantly, this decline occurred during a time of rapid population growth. Thus, the percentage of the population that is poor dropped from 27% to 3%.

- Similarly, in India, population survey data reveals a decline from 330 million poor (51% of the population) in 1980 to 259 million (25% of the population) in 1999.

- Figure 3: Poverty has declined according to China’s and India’s poverty lines (See figure 3 in attached .doc file.)

- According to household surveys in China, the number of people with incomes below the Chinese national poverty line declined from 250 million in 1978 to 34 million in 1999. Over 200 million people were raised out of poverty during that 20 year time period.

- Measured against their own poverty lines (see Map 2, p. 8), China and India have experienced declines in both the numbers and percentage of the poor (see Figure 3 in .doc file attached above).

- On the other hand, as the regional comparison below indicates, the number of poor in Africa increased over the same period.

- In the last several years, however, the number of poor in Africa has begun to decline.

- Table 3: Number of People Living on Less than $1.25/day (millions)

-

1981 1990 1999 2005 2008 East Asia & Pacific 1,096 926 656 332 284 Sub-Saharan Africa 205 290 376 395 386 - Source: World Bank Poverty and Inequality Database http://databank.worldbank.org/Data/Views/Reports/TableView.aspx (April 30, 2012.)

- Nonetheless, African countries, consistently and in great disproportion, still occupy the occupy the bottom positions in standard of living rankings of world nations. (See Table 1, above.)

- In the last several years, however, the number of poor in Africa has begun to decline.

- The decline in the poverty numbers shown in figure 2 (up to 1998) is the result solely of developments in China and India.

- Until recently, world trends in extreme (absolute) poverty were primarily a combination of poverty reduction in Asia and poverty increases in Africa.

- Impressive poverty reduction in Asia has occurred not only in China, but also in Vietnam, Indonesia, and to a lesser extent Bangladesh.

- As data from the first decade of the 20th century has become available, demographers are finding the encouraging news that even the seemingly intractable poverty that plagues Africa may be starting to give way.

- The World Bank’s 2010 report (2008 data) of apparently declining poverty numbers was echoed by UN researchers in 2012 (2010 data).

- The number of poor in the world peaked around 1980 at an estimated 1.4 billion.

- Historically, changes in absolute poverty have been indicated by a population’s increased or decreased ability to acquire particular basic goods and services.

- Economic growth is the key to reducing absolute poverty.

- There are two methods of reducing the number of poor: one is to redistribute income from the rich to the poor, and the other is economic growth.

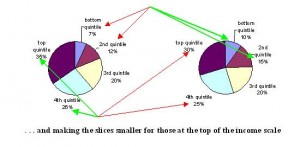

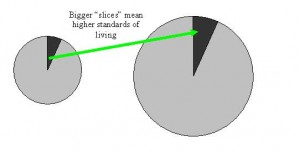

- Using a pie analogy helps to explain the two alternatives. (See Figures 4 and 5 below.)

- If we think of the economy as a pie, reducing poverty by redistributing income (reducing income inequality) is analogous to giving the poor a bigger slice of the pie (See Figure 4.) while reducing poverty through economic growth means making the pie bigger. When that happens, the poor have a bigger slice even if the relative size of the slices doesn’t change. (See Figure 5.)

- Figure 4: Redistribution reduces poverty by giving the poor a bigger “slice of the pie,” and making the slices smaller for those at the top of the income scale.

- Figure 5: Economic growth improves the lives of the poor by making the pie bigger.

- If we think of the economy as a pie, reducing poverty by redistributing income (reducing income inequality) is analogous to giving the poor a bigger slice of the pie (See Figure 4.) while reducing poverty through economic growth means making the pie bigger. When that happens, the poor have a bigger slice even if the relative size of the slices doesn’t change. (See Figure 5.)

- The case for redistribution is based on the persistence of a significant income gap between the rich and the poor in market countries. University of California Professor Roger Ransom explains that perceptions of poverty are based on people’s comparisons of their own material well-being to that of others around them. While we focus on absolute poverty, Prof. Ransom’s reminder about the importance of relative poverty cannot be dismissed.

- “The definition of who is ‘poor’ must ultimately depend on the relative standing of the people in their own community. . . . the ‘poor’ as those who are in a situation where their income . . . places them at the bottom of the income and wealth distribution.” (Ransom, 1)

- Ransom warns, eloquently and convincingly, that if economic growth assures a minimal level of well-being while allowing great disparities in living standards, it fails to adequately address poverty.

- “The argument that economic growth unambiguously helps the poor focuses attention on the provision of some basic level of ‘wants.’ Nontheless, while capitalism may have made a great many people much better off, it has not removed the wide disparity of choices within societies. Lost amid the acclaim for capitalism as a successful engine of growth is the unnerving fact that the expansion of output has not benefitted everyone equally, and growth has been uneven.” (Ransom, 3)

- Pointing to the United States, he notes the persistence of income inequality in our nation’s history.

- There has been no evidence of long-term decline in income inequality in the past 150 years.

- Among developed countries, the United States ranks near the bottom in terms of the percent of income going to the poorest 10% of the population. (See Table 4 in attached .doc file.)

- While redistribution is intuitively appealing as a solution to poverty in a world with great disparities of wealth, there is little historical evidence that redistribution has ever resulted in sustained reductions of poverty

- Figures 6 and 7, below, exemplify the type of evidence offered to question the effectiveness of redistribution and to make the case for economic growth as the best remedy for poverty. (See Figures 6 and 7 in attached .doc file.)

- In Figure 6, the quintiles were created by ranking 103 nations from richest to poorest (based on GNI per capita), and then dividing them into 5 equal groups. (See Table 4, above.)

- The resulting graph tells us that, for example, the average share of total income received by the poorest 10% of the population in the nations in the top quintile (represented by the dark green bars to the far right), was 2.8% in 2004. For the poorest 20%, the average income share in nations in the top quintile was 7.5%. For the bottom quintile, the poorest 10% received an average of 2.2% of their country’s total income and the poorest 20% received an average of 5.5%.

- Regardless of whether the difference in share percentage among quintiles is statistically significant, it is clear from the graph that the share going to the poor is larger in the top quintile of nations. The shares are smaller in the quintiles that included countries with lower per capita incomes, indicating that even in terms of income distribution, the poor do better in rich countries.

- We find the same general result – that the poorest 10% of the population receives only 2-3% of national income — even if we use different criteria to construct the quintiles of nations. While Figure 6 is neutral as to the economic institutions of different nations; in Figure 7, below, the quintiles were constructed on the basis of institutional characteristics.

- The Frasier Institute created 5 quintiles by ranking nations not in terms of per capita income, but in terms of the strength of their capitalist institutions, or degree of “economic freedom.” Those economies in the top quintiles of the ranking (to the right of the graph) have more open, capitalist institutions. Those nations in the bottom quintiles (to the left) have greater government control over the economy, including greater redistribution.

- Figure 7 strengthens the conclusions derived from Figure 6 — that the world’s poor receive from 2 – 3% of their nations’ income and that endeavoring to reduce poverty through redistribution has not produced increases in well-being beyond those experienced by the poor in nations where little or no redistributive efforts are made.

- The Frasier Institute created 5 quintiles by ranking nations not in terms of per capita income, but in terms of the strength of their capitalist institutions, or degree of “economic freedom.” Those economies in the top quintiles of the ranking (to the right of the graph) have more open, capitalist institutions. Those nations in the bottom quintiles (to the left) have greater government control over the economy, including greater redistribution.

- Using a pie analogy helps to explain the two alternatives. (See Figures 4 and 5 below.)

- Historically, the more successful way to reduce poverty has been policies that promote economic growth. In our analogy, that would mean increasing the size of the pie. (See Figure 5.

- This situation can be summed up in the saying “A rising tide raises all ships.

- With economic growth, the poor are better off in absolute terms (their slice of pie is bigger) even if income distribution – and their relative poverty – doesn’t change.

- For example, income distribution is more equal in Tanzania than in the United States. However, the fact that the U.S. has experience sustained economic growth and Tanzania has not – U.S. gross national income ($14,636 billion) is 600 times greater than Tanzania’s ($23 billion) – means that the poorest 20% of the U.S. population has an average per capita income 75 times that of the poorest Tanzanians.

- Two hundred years ago, per capita incomes in different parts of the world were relatively similar. But some locations – notably the U.S. and western Europe – experienced sustained economic growth over long periods of time. It is that growth rather than the degree of income inequality that resulted in the poor of western economies being relatively wealthy by the absolute standard of world poverty.

- Further evidence comes from contemporary data showing that when developing countries experience periods of economic growth, they also experience significant reductions in poverty. (See Figure 9 in attached .doc file.)

- Since 1990, China’s has been the most rapidly growing economy in the world, and the nation has achieved impressive poverty reduction.

- In Bangladesh, India, Uganda, and Vietnam, there has also been a tight link between the rate of economic growth and the rate of poverty reduction.

- The World Bank’s India Poverty Project used consumption data from 35 national sample surveys (1951-94) to study the relationship between the standard of living of the poor and variables within the Indian economy as a whole. (http://www.worldbank.org/poverty/data/indiapaper.htm)

- The findings support the generalization that economic growth, rather than income redistribution, is the key to alleviating poverty. The World Bank researchers concluded that:

- “. . . India’s poor. . . have generally gained from economic growth, and lost from contraction. . . . The net gains to the poor since the early 1970s can be attributed in large part to economic growth – redistribution changed little from the point of view of the poor, although it appears to have been more important in the 1950s and 60s when there was less growth. The results offer support for the view that a stable macro-policy environment, combined with micro-policy reforms conducive to economic growth, can help greatly in reducing absolute poverty in India.”

- The findings support the generalization that economic growth, rather than income redistribution, is the key to alleviating poverty. The World Bank researchers concluded that:

- While the recent success in India testifies to the primacy of economic growth over redistribution in reducing poverty, the case is made stronger by a 2002 study of Vietnam showing that economic growth can reduce absolute poverty even when income inequality is increasing.

- “Vietnam enjoyed high rates of economic growth in the 1990’s. One consequence of this growth was a remarkable decrease in the rate of poverty, from 58% of the population in 1992-93 to 37% in 1997-98 (General Statistical Office, 2000). Yet over the same time period inequality rose . . . [as] wealthier Vietnamese households experienced greater increases in per capita consumption expenditures than did poorer households.” (Glewwe and Nguyen 1-2).

- Researchers Glewwe and Nguyen added the important insight about the composition of income inequality – an insight that is often overlooked – that the composition of the lower income quintiles changes over time.

- “Depicting the consumption expenditures of the rich as growing at a much faster rate than the consumption expenditures of the poor is somewhat misleading. It is very unlikely that all of the households that were in the poorest 20% of the population in 1992-93 were again in the poorest 20% in 1997-98; some of them moved up into wealthier groups.” (1-2)

- Researchers Glewwe and Nguyen added the important insight about the composition of income inequality – an insight that is often overlooked – that the composition of the lower income quintiles changes over time.

- “Vietnam enjoyed high rates of economic growth in the 1990’s. One consequence of this growth was a remarkable decrease in the rate of poverty, from 58% of the population in 1992-93 to 37% in 1997-98 (General Statistical Office, 2000). Yet over the same time period inequality rose . . . [as] wealthier Vietnamese households experienced greater increases in per capita consumption expenditures than did poorer households.” (Glewwe and Nguyen 1-2).

- There are two methods of reducing the number of poor: one is to redistribute income from the rich to the poor, and the other is economic growth.

- Summary

- In summary, then, the most commonly observed patterns, world-wide, indicate that attacking absolute rather than relative deprivation is the key to reducing poverty:

- Sustained growth always goes hand-in-hand with poverty reduction.

- There is little evidence correlating shifts in income distribution to long-term poverty reduction

- When shifts in income distribution do occur, they tend to affect the speed rather than the magnitude of poverty reduction.

- Knowing the what, where, and who of poverty allows us to turn our attention to whether capitalism is an effective tool for alleviating it

- To answer the question, “Is Capitalism Good for the Poor?” by trotting out theoretical models would display callous disregard for the human misery. The question demands that we begin with the empirical evidence, presented in this outline, about those places where poverty is in retreat and those places where it is not.

- What explains the rising standard of living in places as different as China, India, and Uganda? If we examine their record of change, will we discover common cause or serendipity?

- China and North Korea are both communist nations; is there a reason that communist Chinese standards of living are rising and communist North Koreans starve – or is it fate? Does the communist label reflect uniformity or does it obscure explanatory differences?

- The investigation of the relationship between capitalism and absolute poverty begins, therefore, with the statistical and graphic picture painted above. Knowing what and where poverty is, where it is receding and where it flourishes, is prerequisite to the analysis of capitalist institutions that begins in Lesson 2.

- In summary, then, the most commonly observed patterns, world-wide, indicate that attacking absolute rather than relative deprivation is the key to reducing poverty:

Conclusion to Lesson 1, Part 1

Graphs, charts, tables and statistics are essential tools in studying poverty, but they carry with them the danger that the numbers – GDP per capita, infant mortality, life expectancy – dull our perception of human suffering. Similarly, in representing change as tiny dips and bumps in trend lines on graphs, we risk trivializing the life-changing reality that economic growth is the relentless cure for poverty.

“. . . [S]tatistics cannot capture the transition from poverty to wealth. To apply generally to the myriad products and services produced in even a simple economy, statistics have to be stated in units of money. Money is the common measure of economic quantities, no matter what the differences in the products or services being measured may be. Hence statistics would be the same if economic growth consisted in producing more and more of the same goods and services as they would if economic growth consisted – as it does – of changing the whole life-style of a society and drastically altering the goods and services it produces and consumes.

Even at the beginning of economic expansion, there are changes in what people consume, in the work they perform, and in their overall manner of living. In the West, the initial changes were pathetically small – the addition of a few vegetables and a little meat to the average diet and the shift from wooden shoes to leather – and overall numbers could give a fair idea of what was happening. But as Western expansion continued, the lives of human beings were completely changed. Early years spent at work became early years spent at school. A life of work on the manor or farm became a life of work in an urban trade, a factory, or a profession…. It may be true of individuals that the rich differ from the poor only in having more money, but in the case of societies, the rare examples we have of rich societies differ from the poor not simply in having a higher per-capita gross national product, but in creating an entirely different life for their members” (Rosenberg and Birdzell 4).

The caveats duly noted, what we usually have to work with are statistics, and it is important for students to recognize them for what they are – tools that aid understanding – rather than unassailable purveyors of truth. The classroom support materials, “KWL” and the “Poverty Web Quest,” introduce students to various definitions and descriptions of poverty, helping them to discover the strengths and limitations of statistical data in painting an accurate and useful picture of the world’s poor. Using these activities as an introduction to world poverty as an economic issue will:

- Focus students’ attention on world (as opposed to American) poverty by presenting the distinction between relative and absolute poverty;

- Help students acquire the conceptual and statistical tools to describe their own mental pictures of world poverty; and

- Promote the development of a common vocabulary to serve as the basis for students’ ensuing class discussions of capitalism and poverty and their individual answers to the question of whether capitalism is good for the poor.

Supplemental Materials

- Appendix 1: Relative Poverty and Distribution of Income (download .doc file including charts and figures, 2012 revision)

- Appendix 2: Social Indicators of Poverty (download .doc file including charts and figures, 2012 revision)

- Classroom Activity: What is Poverty? – A KWL Exercise

- Classroom Activity: WebQuest – What Is Poverty and Who Are the Poor?

Part 2 continues the work of creating a common vocabulary: Part 2: Capitalism: Institutional Building Blocks

- Historical Overview (2012 update)

- Lesson 1, Part 1: Defining Terms – Poverty and Capitalism

- Lesson 1 Activity: What is Poverty? A KWL Exercise

- Lesson 1 Activity: What is Poverty and Who are the Poor? A WebQuest

- Lesson 1 – Defining Terms: Poverty and Capitalism, Part 2

- Lesson 1, Part 2 Activity: Will the Real Capitalism Please Stand Up?

- Lesson 2: Property Rights and the Rule of Law

- Lesson 2 Activity: You’re the Economist

- Lesson 3: Beneficiaries of Competition

- Lesson 3 Activity: The More, the Merrier

- Lesson 4: How Incentives Affect Innovation

- Lesson 4 Activity: It’s Not Rocket Science

- Lesson 5: Character Values and Capitalism

- Lesson 5 Activity: The Ultimatum Game

- The Ultimatum Game: Appendix 1

- The Ultimatum Game: Visual #7

- Teacher Guide to Readings

- Reading #1

- Reading #2

- Reading #3

- The Chinese Experiment: Opening Markets Reduces Poverty

- Conclusion and Caveats

FTE: Celebrating 50 Years of Excellence in Economic Education

2025 is a special year for the Foundation for Teaching Economics (FTE), as we celebrate our 50th anniversary. In 1975,…

The Economic Way of Thinking: The Key to Financial Literacy

Professor Jamie Wagner discusses how economics is the key to financial literacy. She is a Professor and Teaching Fellow with…

FTE Staff Spotlight – John Buck

As society evolves and transforms, so must world leaders – a fact that John Buck is aware of and has…